Photo by Pedro Ramos on Unsplash

The threat of homelessness is an extremely visceral fear. The lack of a safe place to sleep, eat, shelter from poor weather and gather with those closest to us should be a basic right that every individual sees realised. However, for thousands of children their home is just a hope. In the meantime, they might sleep in mouldy, cold rooms, while sometimes sharing a hotel bed with several siblings with nowhere to play or do homework.

At the end of February this year, the government released new statistics for July to September 2024 showing that 70,450 households in London are in Temporary Accommodation. Focusing exclusively on all households with children across the country in TA, 58% are in London alone. As Shelter, recently highlighted, 164,040 children are currently in TA and 92,850 or nearly 3 in 5 children in TA are in London. These children are not well captured in HBAI data, which is used to create child poverty statistics for the country. That could mean that nearly tens of thousands of children are missing from the estimated 700,000 children believed to be in poverty across the capital. We also know that children are being moved outside of their local borough or even outside of the city entirely, but we don’t know how many.

With the equivalent of one child in every classroom in London currently living in temporary accommodation, and 14,885 young people presenting as homeless to their local council across the city in 2023-24 figures, it is clear that all levels of government across London must take the intersection of the housing crisis and child poverty very seriously.

Gathered evidence shows that child poverty can be a predictor for adult homelessness and is almost always a co-existing reality for families facing the threat of homelessness.

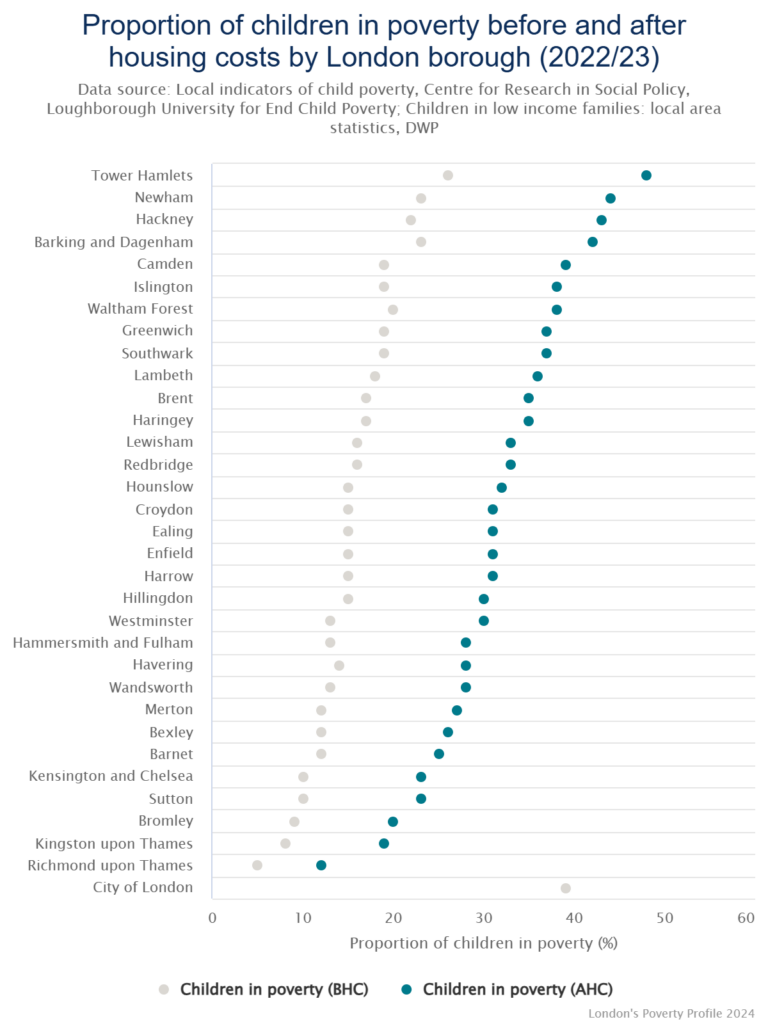

Trust for London’s 2022/23 data on child poverty rates after housing costs show significant jumps when housing costs are accounted for as the chart below shows. The affordable housing crisis in London and the hundreds of thousands of children experiencing poverty must be viewed in tandem. If we want to seriously prevent child poverty from causing long-term harm to children, we need to build appropriate, truly affordable homes fit for families who live in our community urgently.

The challenge though to quickly improve the lives of families is to provide the services they need when the threat of homelessness first looms. There are particular groups who face specific barriers when navigating personal crisis. For a parent who is threatened with domestic violence or a single parent with threats from debt collectors or joblessness due to unpaid caring responsibilities, holistic support is needed to help prevent and reduce the likelihood that they are unable to stay or move into a permanent home quickly. Other families are essentially forced into homelessness after their application for asylum is approved and they’re granted refugee status. These families often have little to no social and financial capital. Those still in a visa application process also face costly fees and limited social security support should they need it. And if a person has grown up in poverty and either loses their home or must leave their current place as a young person, their age may limit both their eligibility for support and prioritisation for what little help they can request.

Effective interventions must tackle both the broad supply challenges as well as the specific individual circumstances of Londoners. If change isn’t built on understanding of individual needs, it will fail to create systemic change.

Certainly, the evidence is clear that building more truly affordable social housing is the cure. At the same time, we also need to inoculate ourselves against the disease of child homelessness in London urgently. This is a public health crisis and a moral indictment.

We are currently leading a project focusing on the key moments when homelessness should and could be prevented. We believe that some crucial conversations need to be had about protecting families from homelessness and providing appropriate support to shorten or prevent experiences of homelessness. The issues are complex, but inaction is costly. Children have significant health, academic and social risks if we do not act quickly. We’re privileged to be working with Cardinal Hume Centre and New Horizon Youth on this project. Together we’re gaining insight from three particular groups to understand what policies need to be put in place while the houses are still being built.

We’re currently interviewing young people with experience of homelessness as a minor or young adult, migrant families and single parent, women led families. We are holding these interviews across March and April. If you know of someone who might like to take part, please do get in touch.

We aim to share our findings in summer 2025 and invite political leaders and civil servants to engage in important conversations about how we can support families to reduce the backlog of cases where families are living in unacceptable circumstances and children are growing up without a home.