4in10 Newsletter 26.6.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

4in10 Newsletter 12.6.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

4in10 Newsletter 29.5.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

4in10 Newsletter 15.5.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

4in10 Newsletter 17.4.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

4in10 Newsletter 3.4.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

4in10 Newsletter 20.3.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

The tragic relationship between child poverty and homelessness in London

Photo by Pedro Ramos on Unsplash

The threat of homelessness is an extremely visceral fear. The lack of a safe place to sleep, eat, shelter from poor weather and gather with those closest to us should be a basic right that every individual sees realised. However, for thousands of children their home is just a hope. In the meantime, they might sleep in mouldy, cold rooms, while sometimes sharing a hotel bed with several siblings with nowhere to play or do homework.

At the end of February this year, the government released new statistics for July to September 2024 showing that 70,450 households in London are in Temporary Accommodation. Focusing exclusively on all households with children across the country in TA, 58% are in London alone. As Shelter, recently highlighted, 164,040 children are currently in TA and 92,850 or nearly 3 in 5 children in TA are in London. These children are not well captured in HBAI data, which is used to create child poverty statistics for the country. That could mean that nearly tens of thousands of children are missing from the estimated 700,000 children believed to be in poverty across the capital. We also know that children are being moved outside of their local borough or even outside of the city entirely, but we don’t know how many.

With the equivalent of one child in every classroom in London currently living in temporary accommodation, and 14,885 young people presenting as homeless to their local council across the city in 2023-24 figures, it is clear that all levels of government across London must take the intersection of the housing crisis and child poverty very seriously.

Gathered evidence shows that child poverty can be a predictor for adult homelessness and is almost always a co-existing reality for families facing the threat of homelessness.

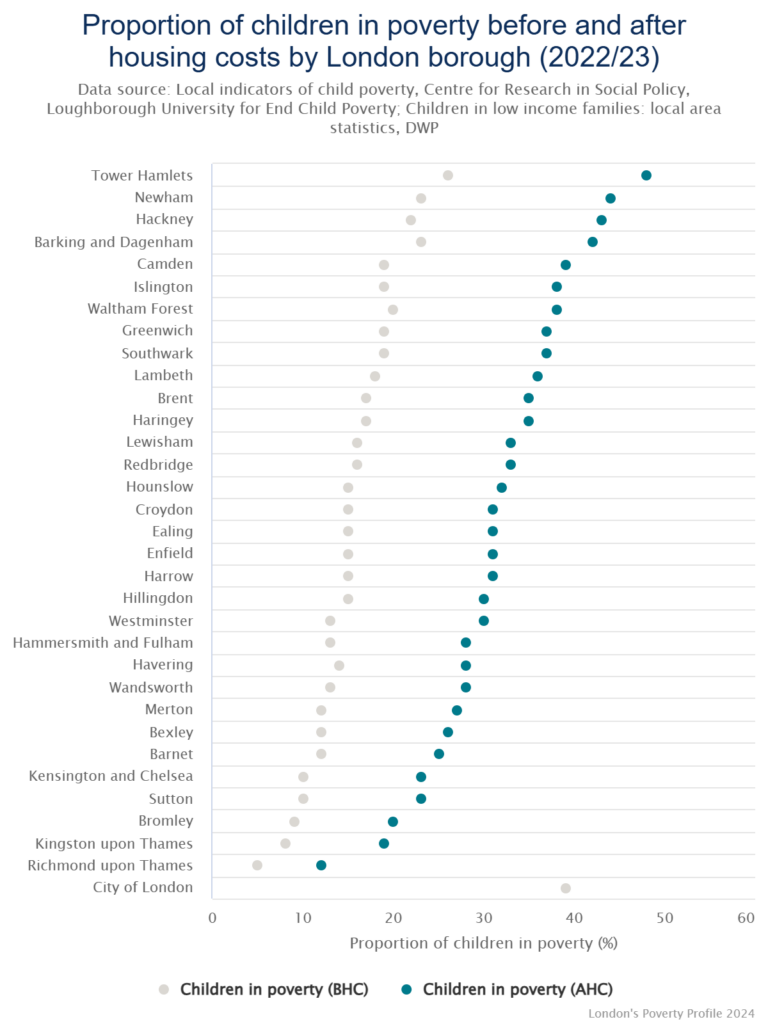

Trust for London’s 2022/23 data on child poverty rates after housing costs show significant jumps when housing costs are accounted for as the chart below shows. The affordable housing crisis in London and the hundreds of thousands of children experiencing poverty must be viewed in tandem. If we want to seriously prevent child poverty from causing long-term harm to children, we need to build appropriate, truly affordable homes fit for families who live in our community urgently.

The challenge though to quickly improve the lives of families is to provide the services they need when the threat of homelessness first looms. There are particular groups who face specific barriers when navigating personal crisis. For a parent who is threatened with domestic violence or a single parent with threats from debt collectors or joblessness due to unpaid caring responsibilities, holistic support is needed to help prevent and reduce the likelihood that they are unable to stay or move into a permanent home quickly. Other families are essentially forced into homelessness after their application for asylum is approved and they’re granted refugee status. These families often have little to no social and financial capital. Those still in a visa application process also face costly fees and limited social security support should they need it. And if a person has grown up in poverty and either loses their home or must leave their current place as a young person, their age may limit both their eligibility for support and prioritisation for what little help they can request.

Effective interventions must tackle both the broad supply challenges as well as the specific individual circumstances of Londoners. If change isn’t built on understanding of individual needs, it will fail to create systemic change.

Certainly, the evidence is clear that building more truly affordable social housing is the cure. At the same time, we also need to inoculate ourselves against the disease of child homelessness in London urgently. This is a public health crisis and a moral indictment.

We are currently leading a project focusing on the key moments when homelessness should and could be prevented. We believe that some crucial conversations need to be had about protecting families from homelessness and providing appropriate support to shorten or prevent experiences of homelessness. The issues are complex, but inaction is costly. Children have significant health, academic and social risks if we do not act quickly. We’re privileged to be working with Cardinal Hume Centre and New Horizon Youth on this project. Together we’re gaining insight from three particular groups to understand what policies need to be put in place while the houses are still being built.

We’re currently interviewing young people with experience of homelessness as a minor or young adult, migrant families and single parent, women led families. We are holding these interviews across March and April. If you know of someone who might like to take part, please do get in touch.

We aim to share our findings in summer 2025 and invite political leaders and civil servants to engage in important conversations about how we can support families to reduce the backlog of cases where families are living in unacceptable circumstances and children are growing up without a home.

4in10 Newsletter 6.3.25

Read the latest newsletter here.

To get this directly to your inbox every fortnight please do join us.

Visit to Restorative Justice for All

One of the best parts of the role of community outreach officer for 4in10 is the privilege of being able to visit our extraordinary members and this has led to some truly fantastic experiences.

Whether it is being part of the series of campaign events put together by Southall Community Alliance, watching the presentation of new bleed control kits, donated by anti-knife crime charity Bin Knives, Save Lives or being part of community information events run by Poplar Harca housing association, this job continues to give me the chance to really experience the hard work of our incredible membership and has given me a real sense of hope.

Given this I thought it would be good to write about one of these events to give you a flavour of the experience.

A couple of weeks ago I was lucky enough to visit Restorative Justice for All (RJ4All)’s Rotherhithe Community Centre whilst they were doing their Wellbeing Circle.

RJ4All is a charitable international institute with a mission to address power abuse, conflict, and poverty through the use of restorative justice values and practices. The RJ4All Rotherhithe Community Centre serves as a vital hub for community empowerment and social connection at the local level.

As RJ4All’s Community Centre is always doing events, so for me it was originally more the date I was available to go than what activity I was going to be part of, but I was so glad I chose that day!

When I arrived, I was instantly made to feel completely welcome and shown around their centre. This was a very friendly building made up of a few side rooms, an office, a small kitchen and a small meeting room with sofas, tables, chairs and toys for children.

I was the first visitor to join but the session quickly filled up and by the time we were ready to go there were maybe 10 of us (all women). It was only at this point that I was grew to understand the nature of the event.

Our team leader explained to us that the idea was that each week the wellbeing circle explored a thought-provoking topic with the leader posing questions within it. She then apologised as it was her first week – not that you would have known she was brilliant.

I would not say I was cynical about the model – group therapy has been shown to do some amazing things but I was unsure how I would find it with not knowing anyone or indeed anything about the event but any anxieties I had were soon to be proved wrong.

The topic under discussion was ‘forgiveness’. First we were asked to explain in turn what we understood forgiveness to mean and then went on to explore times where we had each grappled with forgiveness.

As we went round the circle the comments of my fellow participants began to really touch something in me and as the evening went on I found myself talking about things and feeling emotions that I would never have thought about. And this, plus being with others while they explored sometimes very personal things profoundly touched me.

I came away from that extraordinary event feeling incredible, refreshed and if possible lighter; like I had been on a big therapy session. I would recommend this experience to anyone!

RJ4All’s Wellbeing Circles promote its overall vision of building the world’s first restorative justice postcode by providing a first line of mental wellness support to the community, strengthening relationships within the area, and fostering community cohesion in SE16.If anyone else would like to learn more about RJ4All you can go to their website here [I’ll include a link when it goes live].