Guest Blog with Z2K on the damaging impact of London's temporary accommodation crisis

Photo by Cyrus Crossan on Unsplash

Photo by Cyrus Crossan on Unsplash

Hear from Louise* and Miracle, two peer researchers with lived experience of temporary accommodation (TA) who co-produced Z2K’s research report ‘Frozen in Time’. The researchers interviewed people living in TA in Westminster about the issues they face and the impact that living in TA is having on peoples’ lives. The research was launched last month at an event in Parliament hosted by Rachel Blake, MP for Cities of London and Westminster.

Miracle: My first experience of homelessness and temporary accommodation was in London during my late teens for about two years. For a young man with the ambition to hopefully do well in the world and succeed through education, those two years for me were really traumatizing (fighting forces of derailment with a strong will and focus to triumph through). The overall experience I had during that period of time involved living in bad housing conditions (mould, damp and pests) causing health issues, as well as the impact of burglaries. However, I went through adversity those two years and conquered it with cheerful spirits of hope for a better day someday. Since this time, I have had a nomadic existence because I had nowhere that I could call home in the UK. I moved from TA to a mixture of student accommodation and privately rented accommodation. More recently, I have found myself back in TA, placed in a hotel ‘out-of-borough’.

Louise: I lived in TA as a single parent placed out-of-borough. It felt like screaming in a sound-proofed room, hoping someone might hear. I felt exhausted from fighting to pin down who was responsible for the infestations and damp in the property. For my child, living in TA meant having a stressed mother whose spare time was spent chasing the council, growing up in an environment which did not allow pictures on the wall, pets, or any self-expression or personalisation – and no playdates due to the damp and disrepair.

Miracle: It has been a rewarding experience being a peer researcher on the Z2K temporary accommodation project. Working on the project and meeting like minds with shared experiences was for me a great opportunity to help dig into the heart of the TA experiences which many in Westminster are currently having. It has been satisfying to try to bring this reality closer to the eyes of decision-makers at Westminster City Council.

Louise: Interviewing people who had been placed in TA by Westminster City Council as part of the research project was the first time I had spoken to anyone else in TA about their experience, and the interviews immediately made me feel less isolated and more human again. I found it validating and cathartic to speak to others facing similar difficulties.

Miracle: It is clear to see from the findings that people living in Westminster TA desire more empathy and understanding.

Louise: In temporary accommodation you are always on the verge, on tenterhooks, never knowing when you’ll get told to leave. I felt helpless living out-of-borough, unable even to vote for the Westminster councillors who held my housing future in their hands. Then there is the stigma you fear if you share this with schools or GPs; the assumption you must have done something wrong to be in TA to begin with.

Miracle: There are a number of areas where change is needed, such as in the council’s engagement and communication with people.

Louise: All Westminster schools and GPs should read this report so they understand how TA affects their service users. Similar to my own experience, the vast majority of people I interviewed did not feel that their needs were met or understood. Whether it was complaints about damp and mould adversely exacerbating their health problems, or traumatised survivors of domestic abuse being placed in unsuitable accommodation, the common problem was the lack of communication and engagement on the part of the council. This left the interviewees, mostly women, feeling forgotten and as if they don’t matter.

Miracle: We need to see a change in the way in which people living in TA are often seen and treated.

Louise: The uncertainty and the worry of not knowing where or when they might be moved on caused families stress and insomnia, which affected their mental and physical health. This in turn affected school or work outcomes, despite trying their utmost to do well and succeed. Households needing temporary accommodation appear to be looked down on.

Miracle: For so many, living in TA is not temporary. Therefore, improving TA standards is surely an area where change is vital. I believe that the report will help to bring a dose of reality to the current understanding of temporary accommodation at Westminster City Council, so that there can be a different tomorrow.

Louise: I believe that if the council staff had carried out the interviews we did, and experienced the resilience and tenacity of these people, then they would treat them with more respect, inclusion and engagement. Meaningful dialogue, not stonewalling, is what is needed to free people living in temporary accommodation from the state of limbo that they find themselves in.

*Not her real name

The tragic relationship between child poverty and homelessness in London

Photo by Pedro Ramos on Unsplash

The threat of homelessness is an extremely visceral fear. The lack of a safe place to sleep, eat, shelter from poor weather and gather with those closest to us should be a basic right that every individual sees realised. However, for thousands of children their home is just a hope. In the meantime, they might sleep in mouldy, cold rooms, while sometimes sharing a hotel bed with several siblings with nowhere to play or do homework.

At the end of February this year, the government released new statistics for July to September 2024 showing that 70,450 households in London are in Temporary Accommodation. Focusing exclusively on all households with children across the country in TA, 58% are in London alone. As Shelter, recently highlighted, 164,040 children are currently in TA and 92,850 or nearly 3 in 5 children in TA are in London. These children are not well captured in HBAI data, which is used to create child poverty statistics for the country. That could mean that nearly tens of thousands of children are missing from the estimated 700,000 children believed to be in poverty across the capital. We also know that children are being moved outside of their local borough or even outside of the city entirely, but we don’t know how many.

With the equivalent of one child in every classroom in London currently living in temporary accommodation, and 14,885 young people presenting as homeless to their local council across the city in 2023-24 figures, it is clear that all levels of government across London must take the intersection of the housing crisis and child poverty very seriously.

Gathered evidence shows that child poverty can be a predictor for adult homelessness and is almost always a co-existing reality for families facing the threat of homelessness.

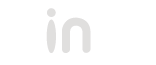

Trust for London’s 2022/23 data on child poverty rates after housing costs show significant jumps when housing costs are accounted for as the chart below shows. The affordable housing crisis in London and the hundreds of thousands of children experiencing poverty must be viewed in tandem. If we want to seriously prevent child poverty from causing long-term harm to children, we need to build appropriate, truly affordable homes fit for families who live in our community urgently.

The challenge though to quickly improve the lives of families is to provide the services they need when the threat of homelessness first looms. There are particular groups who face specific barriers when navigating personal crisis. For a parent who is threatened with domestic violence or a single parent with threats from debt collectors or joblessness due to unpaid caring responsibilities, holistic support is needed to help prevent and reduce the likelihood that they are unable to stay or move into a permanent home quickly. Other families are essentially forced into homelessness after their application for asylum is approved and they’re granted refugee status. These families often have little to no social and financial capital. Those still in a visa application process also face costly fees and limited social security support should they need it. And if a person has grown up in poverty and either loses their home or must leave their current place as a young person, their age may limit both their eligibility for support and prioritisation for what little help they can request.

Effective interventions must tackle both the broad supply challenges as well as the specific individual circumstances of Londoners. If change isn’t built on understanding of individual needs, it will fail to create systemic change.

Certainly, the evidence is clear that building more truly affordable social housing is the cure. At the same time, we also need to inoculate ourselves against the disease of child homelessness in London urgently. This is a public health crisis and a moral indictment.

We are currently leading a project focusing on the key moments when homelessness should and could be prevented. We believe that some crucial conversations need to be had about protecting families from homelessness and providing appropriate support to shorten or prevent experiences of homelessness. The issues are complex, but inaction is costly. Children have significant health, academic and social risks if we do not act quickly. We’re privileged to be working with Cardinal Hume Centre and New Horizon Youth on this project. Together we’re gaining insight from three particular groups to understand what policies need to be put in place while the houses are still being built.

We’re currently interviewing young people with experience of homelessness as a minor or young adult, migrant families and single parent, women led families. We are holding these interviews across March and April. If you know of someone who might like to take part, please do get in touch.

We aim to share our findings in summer 2025 and invite political leaders and civil servants to engage in important conversations about how we can support families to reduce the backlog of cases where families are living in unacceptable circumstances and children are growing up without a home.

Child Poverty in London: a societal problem calls for community-led solutions (Part 3)

Our Research and Learning Officer, Emily, discusses three questions on the issue of child poverty in London. This piece is split across three blog posts:

- What is child poverty?

- What’s the state of child poverty in London?

- How do we end child poverty?

How do we end child poverty?

This is a big task. Let’s say tomorrow the government printed money and gave it to every family under the relative poverty line and promised to keep sending them money to ensure they never fall below that line, would child poverty end? If that question were posed to different politicians and members of the public, I’m sure several revealing answers would emerge. The reality is that things are much more complicated than just money. But as a start, money really does help. The £20 per week uplift to Universal Credit that was temporarily put in place during the pandemic pulled 400,000 children out of poverty. Other estimates claim that making this permanent would lift 500,000 children out of poverty. So money must be part of our child poverty strategy. So too would other public systems. Having an adequately sustained NHS and mental health services would keep children and their parents well, which cuts costs, both in terms of health itself and the knock-on effects of poor health.

Flexible working could also be seen as a support structure to allow adults, particularly women, to work consistently and progress in their careers while also caring for their children. And there’s also the housing issue. In London housing is incredibly expensive and too many affordable options are unsuitable. Guaranteeing affordable homes for everyone can be seen as part of a child poverty strategy.

So it’s about money, but it’s also about a community-based strategy. We need to eradicate the shame. There is no reason to judge people. Ending shame is not ending personal responsibility. Ending child poverty requires us to work together. It means believing the evidence that shows the causes of inequality and poverty are multiple and intersecting. It also means, perhaps, as a community taking on the shame that we don’t yet know how to support each other well enough. Privilege and discrimination has blinded many of us to our own personal responsibility. We can do better at that, but we need to be honest about our role and how we can learn to support each other more holistically and with respect.

4in10, London’s Child Poverty Network is committed to supporting collaborative working. We are a network of organisations who want to see an end to child poverty in London. There is so much brilliance bottled up in the children of this city. When we invest in them and make sure each of them has an opportunity to thrive, then we will begin to see transformations that we will all benefit from.

London’s Child Poverty Alliance, the policy sub-group of London’s Child Poverty Network has identified four key areas that can be catalysts for change. In our Manifesto, we outline current areas of inequality and systemic failure that are points of potential transformation that could ultimately bring an end to child poverty in London. Secure, adequate income will give families the resource to access what they need. All across London, our homes are fundamental to our health and wellbeing. When our homes are of decent quality, the comfort and security they provide enrich our lives and support our mental and physical health. Every child deserves the best start in life, ending child poverty means ensuring every child has access to the early education and childcare to thrive. Lastly, having access to nutritious and reliable food sources so that all children are free from hunger can target one of the essential threats of child poverty. Together, we can make child poverty a way things used to be rather than how we live now if we target these four areas as crucial pinch points of poverty to make London a fairer city for every child.

Child Poverty in London: a societal problem calls for community-led solutions (Part 2)

Our Research and Learning Officer, Emily, discusses three questions on the issue of child poverty in London. This piece is split across three blog posts:

- What is child poverty?

- What’s the state of child poverty in London?

- How do we end child poverty?

What’s the state of child poverty in London?

Unfortunately, the number of children in poverty across London is extremely high. The latest figures from 2021/22 show that London has a child poverty rate of 32.9% according to End Child Poverty Coalition. We expect this to increase when the current year’s figures are released. Experiencing poverty can mean children are only able to afford cheap, unhealthy food. It might mean they skip washing their clothes, bathing and brushing their teeth. It can result in anxiety and isolation, aggressive or regressive behaviour. Being trapped in poverty can lead to a stressful environment at home, where children feel like they need to take on adult responsibilities to help out. While all these things can be true for any child of any household income, the likelihood of overlapping challenges or examples of ‘going without’ can be much greater when a child is in poverty. Parents can be doing the best they can with what they’ve got, but they can’t absorb all of the trauma that impacts them and their families.

How do we respond to child poverty?

The government prioritises helping families get into work. This can be one valuable, effective way to help families in poverty. However, it’s important that context is considered. For one, balancing children’s needs with a work schedule is very difficult. So, for single-parent families flexible, adequate work is crucial. In addition, some parents can’t work because either they or their child is disabled and therefore more support is needed that looks different than paid work. Also, illness needs to be considered as some adults can’t work because they are dealing with an acute illness. Therefore, as a society, we have to think about helping families get support and money in their pockets and community connections that look beyond the paid work route out of poverty.

At 4in10, we talk about supporting organisations who work to end poverty or mitigate its impact. To end child poverty would be to ensure that families have the income they need to cover the essentials. This can look like a robust social security which puts money back into the pockets of families, it can also look like higher pay which increases the incoming funds on a regular basis and it can also take the form of organisational tax breaks or social investment in services so that more support is freely available which reduces the need to ‘buy in’ to participate in local communal activities and opportunities.

In terms of mitigation of the effects of child poverty, again, some specific considerations help draw out this point. Children know when they don’t have as much as others. Children are experts in observation, they learn from seeing and doing and so they know when things are different. When it comes to household finances, they may not know the details or understand the specific issues, but children are capable of knowing when they have less or shouldn’t ask for more. As part of communities all across London, we can help nurture belonging and fairness by making it easy to share resources, reduce additional expenses at school and offer out-of–school activities that are free of charge and sustainably developed and delivered. By making it less about what you can buy and more about where we can belong, the organisations such as youth clubs, art groups, theatres, community organisations, schools and many other community-led programmes help children access support and meaningful relationships with those local to them. This can create a buffer between children and the impact of poverty on their wellbeing. These kinds of services will always be important, even if child poverty disappeared from London. Their existence helps offer important outreach to children and their families. It’s important that these organisations can focus on what they do best, but the current system demands them to follow the money in terms of endless cycles of grant submissions, reporting and project adaptation to keep the budgets balanced. This makes losers out of all of us. Funding can and should be sustainable.

There are steps that all of us can take in our organisations and as individuals to help advocate and implement change. In our Manifesto for a child poverty free London, we outline four key areas that would help reduce child poverty across London. Income, housing, childcare and hunger. These four areas impact us all and in different ways, individuals, businesses, local, regional and national government can help contribute to make the situation better for children. This is not about attributing blame on any one group, but about community-centred and multi-faceted responses to helping improve the lives of children and challenging inequalities when and where we see them.

Child Poverty in London: a societal problem calls for community-led solutions (Part 1)

Our Research and Learning Officer, Emily, discusses three questions on the issue of child poverty in London. This piece is split across three blog posts:

- What is child poverty?

- What’s the state of child poverty in London?

- How do we end child poverty?

What is child poverty?

The very fact that children experience poverty across London reflects the failings of British society to support its youngest members. Children are experiencing poverty because their guardians don’t have enough resource to meet their basic needs. Despite their care givers’ best efforts to protect them, children in poverty can experience the stress and insecurity that stems from not having enough to meet essential needs and some children even take on the practical or emotional responsibility to help alleviate some of the worries of the adults in their household. Children don’t choose poverty. And they can’t choose to end it. They rely on adults in their community, both local and national to make the changes necessary to ensure they, as children, get what they need.

Relative poverty is defined as a household income that is 60% below the median income. While children are in poverty across the country, they may not experience it in the same way. In London, housing costs and childcare costs mean that children in London are more likely to live in unsuitable accommodation and fewer access early years education whereas in other parts of the country, the challenges may be high travel costs or their adult carers experiencing difficulty finding work.

What causes it?

The simple reason for what causes poverty is that household income isn’t enough and is far below the average of many other households. The much more complicated answer is that inadequate income can be the result of an inability to work, poor health, disability, discrimination or unexpected change of circumstances or a combination of challenges that lead to income insecurity. Where it gets really complicated is that accessing adequate income is not a case of simply trying to secure more work because often suitable, paid work is not accessible, for example because of prohibitive childcare costs. This is where narratives around personal responsibility and shame can take root and spring life to inaccurate descriptions as to why some people have enough and others don’t.

Child poverty is caused by both indirect and direct policy decisions related to children. For example, financial budget reductions for schools, youth services and community organisations mean that children are cut off from the services meant to serve them specifically and in turn it’s only those who can afford to pay for those same services that get the high quality opportunities that help shape children’s present experiences to lead to privileged future opportunities. In addition, policies that impact wages, housing and service provision across the country mean that adults can’t access the jobs and support they need, which has a knock-on effect for children. In combination, these circumstances exacerbate inequality making a greater divide between those who can afford to pay extra and those who can’t afford the essentials.

What makes child poverty different?

One of the worst parts of child poverty is that it hurts people at a crucial time in their lives when poverty is integrated into their physiological systems. When their bodies and minds are developing rapidly, and their emotional regulation is dynamically maturing, the trauma that poverty inflicts has a lasting impact. While adults might feel the burden of responsibility, they also have more political influence as voters. Children do not. They can’t work, they can’t vote and they can’t always access the people with power and influence to change. So, they are made to wait and struggle.

4in10 Member Conducts Research on Low-Income Families and SEND Support

Over the past several months, 4in10 has been working with one of our members, Education and Skills Development Group (ESDEG) to support them in creating an excellent report that outlines the importance of their work with low-income ethnic minority families with children who are eligible for SEND support. With a financial contribution from 4in10, Suchismita Majumdar, ESDEG’s Communications & Policy Officer conducted comprehensive interviews and analysis with the ESDEG team to get a sense of the particular needs and challenges children who require SEND support face when they and their parents seek access to additional support.

The report takes an impressive introspective look at the programmes ESDEG offers and the support they give to children and their parents in response to the particular needs of specific ethnic groups, in particular, Somali, Pakistani, Afghan, Indian and Black Caribbean communities.

Their report, available here, shines a light on the situation both for non-white families across London who encounter barriers because of cultural and economic stigma as well as the more widespread scarcity of SEND programmes and professionals in the state school system across London.

The report also includes some key evaluations that ESDEG has identified to help guide them as they plan and implement future programmes, policies and campaigns going forward.

How Poverty Feels

In 2021, 4in10 in partnership with the Greater London Authority commissioned ClearView Research to speak with Londoners to understand what poverty felt like since the Covid-19 pandemic had hit. What Londoners said helps paint a picture of the challenges that so many people face.

All of us across the city have ambitions and there is plenty of opportunity to go around, but it’s been ring-fenced for a small group of people leaving many with too little left. The report showed that with an inadequate social security system, many families found the challenge of gaining secure employment, suitable housing, affordable childcare and everyday costs out of reach. Despite having big dreams, many felt that they were fighting forces beyond their control, an experience compared to flying against gravity.

In 2023, with numerous strikes occurring on a regular basis, it’s clear that workers in many sectors feel they are at breaking point highlighting that the foundations are in need of repair. Basic transportation, health and teaching services are woefully underfunded and lacking investment for innovation and expansion. It’s worth revisiting this report to understand what families are facing today.

Families can’t strike, they have to keep up the fight despite recent data showing that low-income Londoners have faced 21% inflation over the last three years. Families are choosing between heating and eating and the prospect of focusing on career progression when your flat is mouldy and transportation is unaffordable and childcare is inaccessible is an impossible challenge.

What Londoners asked for in the report was for government to make the basics affordable. If childcare, cost of living bills and transportation were affordable then the possibility of families accessing better employment and housing that would enable them to thrive could come to fruition. This is what a good social security system does, it ensures we all have what we need through a social investment for us all. We need policies shaped by all of us to ensure no one gets shut out of decisions that affect them.

Revisiting this report from 2021 is worthwhile because its key findings still hold their weight. That is that poverty is something most of us are concerned about and 85% of us believe that politicians should do more about it.

With local elections just around the corner and London mayoral elections and a General Election on the horizon, it’s worthwhile thinking about making sure politicians hear from you that ending poverty warrants strategic policies. It must be a priority if communities are to thrive, and industries continue to expand providing income sources for Londoners. Flying Against Gravity shows the experiences of Londoners in first-hand accounts that remind us of the emotional toll that is unacceptable.

Together we can do more by demanding lasting change to ensure we all have what we need to soar.

Children with special educational needs and disabled children

4in10 organised a coffee morning in February 2023 that was jointly hosted by staff and parents at Marjory Kinnon School in Hounslow. Rochelle McIntyre, the Family Support and Community Outreach Worker facilitated the discussion and had invited her colleague Jo Stacey, Assistant Head Teacher, Key Stage 2 and Staff Governor as well as a parent to provide first-hand experience.

This mother shared her experiences as a single-parent and the challenges of caring for a child with autism. Throughout the group discussion, a few key costs were mentioned that demonstrate the challenge of parenting and educating children with a learning disability. These include:

- Changing dietary needs and specific food items being essential to meet the sensory needs of the child, these foods are often more expensive or difficult to predict and buy reduced

- Clothing and textures becoming uncomfortable leading to new purchases frequently

- High costs to attend a sensory appropriate gym, averaging £17.50 per visit which swallows up a high proportion of the Disability Living Allowance (DLA) that her son is entitled to

- Taxis across London for appointments as the underground is too overstimulating

- This parent shared that her son often strips off his clothes at home meaning its particularly important to keep the house warm enough, thus adding to the cost of utilities.

The emotional side for parents was also highlighted. A parent in attendance explained that working part time and taking coursework all had to stop because it just became too overwhelming for her and exhausting to keep up. Even when she was able to access a personal assistant, there were still costs associated with the PA taking care of her son or taking him out and about that limited how much her son could do with her PA. Thus, it felt like there were always limitations and challenges as to how much help she could get because the costs keep adding up.

Another parent of a child with autism shared her own experiences and emphasised that practical help is important, but the challenge of supporting and adjusting to the sensory needs of a growing child with autism is always there.

At 4in10, we want to listen to these experiences and share them with those who make decisions that impact children and their parents. We want to highlight the financial and emotional challenges that parents face and the impossible situations that parents with low-incomes encounter when caring for a child with a special need or disability. If you have other thoughts or experiences that you’d like to share, please do get in touch so we can support growing more awareness and social action to advocate for better support of children with varying needs and financial situations.

Research about young people designed by young people for young people

Reflections from Research and Learning Officer, Emily Barker, on an exciting new venture organised by one of our members and taking place across London.

Young Londoners Research Project

For those interested in youth-led research, I’ve got something to share! I came across a brilliant series of projects that our member, Partnership for Young London, is coordinating along with Rocket Science and Young Harrow Foundation. A total of nine research projects are taking place thanks to these partners working with the Greater London Authority who has commissioned ‘a new programme that will fund and support young people, their youth or support workers and their youth organisations to research young people’s views.’

Follow this link to learn more about the Young Researchers Programme and for a description of the nine exciting projects underway. The variety of projects speaks to the scope of creativity and talent of these young people. It’s a thrill to hear how passionate as well as thorough and insightful these young people are about putting in the work to develop new knowledge that will help improve the experiences of young Londoners.

When young people are involved in evaluating and improving the services aimed at them, it can help increase the reach and impact of these services on those who need it most. Many of the projects consider what barriers exist for young people who need to access additional support. Making steps to improve young people’s lives is a key strategy in mitigating the impact , both immediate and long term, of child poverty.

I am especially looking forward to hearing about the findings of the research projects in spring 2023! I can’t wait to learn from their analysis!

Sarah Jones, MP in discussion on the impact of violence and poverty on young people in London

In follow up to a coffee morning 4in10 hosted in early November, I had a chance to speak with Sarah Jones, MP for Croydon who set up the national cross-party campaign against knife crime and is Labour’s Shadow Minister for Policing and the Fire Service. She discussed her experience working to address knife crime and what she’s learned in her role as MP in Croydon.

Our full discussion is available at this link or by clicking on the thumbnail below.

4in10 welcomes discussion from elected representatives from all political parties as they support and collaborate with our network members to implement sustainable, permanent changes to reduce poverty and all its damaging outcomes.

Cost of the Child 2022

According to Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG’s) recent report, ‘Families in 2022 are facing the greatest threat to their living standards in living memory.’ Calculations for the current economic climate show that the cost across 18 years to raise a child is nearly £70,000 for a couple and over £113,000 for a lone parent to cover basic costs. When accounting for childcare and rent, these figures rise to over £157,000 for a couple and £208,735 for a lone parent across the same time period of 0-18 (3).

Childcare alone accounts for 60 per cent of the costs of raising a child for a couple working full time, an increase of 20 percent over the last 10 years (3). A nonworking parent or couple will receive less than half of those costs covered by benefits and even a lone parent earning a median wage would only earn 88% of what is needed to make ends meet (3). Furthermore, the structure of childcare support and the lack of provision for 0-1 year-olds functions as a disincentive even up until the age of 3 making it challenging for lone parents to increase their earnings through higher paying jobs because they will spend too much of their income on childcare costs in their child’s early years (5).

One positive of note is the increase over several years of the ‘national living wage’ which the chancellor has recently confirmed to be raised in April 2023 by 10.1 per cent becoming £10.42 for over 23-year-olds (National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)) as well as an uprate in benefits by the same percentage (Chancellor delivers plan for stability, growth and public services – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)).

However, these benefits are mitigated by the existence of the benefit cap which limits the impact and real take home increase these other changes will have (10). The report offers the example of ‘[a] couple supporting two children and living in private accommodation, for example, is now over £350 a week short of meeting their needs, an increase since 2016 of nearly 60 per cent. This is the result of the benefit cap biting,’ a reality even worse for children with a third child, but unable to access further support because of the two-child limit (10).

Specific to London families, 4in10 has shown that housing and food costs are hitting London families especially hard (Cost of Living Crisis & Children in Poverty: London Spotlight). The cost of a child in London is likely to be higher because of increased costs of childcare, housing and food prices.

Overall CPAG’s report shows that not only has the cost-of-living crisis hit families hard, but that this is a long-term deterioration of support over the past decade that has snowballed this winter. For families in London, the challenges are complex and ways of accessing support can be daunting and confusing. For the organisations supporting these families, this report confirms what we already know, families are being squeezed bone dry to keep their children fed and cared for, there’s is nothing left in the tank, but the opportunity to provide targeted support to families both from the charitable and government sector is abundant. Children are worth every penny of investment, but we need to take seriously the need to advocate for systemic change in how we give every child what they need.