The emotional toll of poverty on children, young people and families

This blog is adapted from a LinkedIn post published by our Strategic Programme Manager, Katherine Hill to mark Mental Health Awareness Week 2025

“I feel anxious all the time, like I’m riding a rollercoaster…”

That’s how one parent in London recently described life with young children.

But it wasn’t sleepless nights or toddler tantrums they were talking about — it was poverty.

This Mental Health Awareness Week, I want to highlight two powerful reports published recently by members of 4in10 London's Child Poverty Network that make something crystal clear: poverty doesn’t just affect bank balances — it affects mental health, emotional resilience, and how people experience the world around them.

Last week, Home-Start London released new research based on interviews with families supported by local Home-Starts across the city. The picture they paint is tough.

- Nearly 9 in 10 families (86%) say that money worries are making parenting harder.

- 81% feel anxious or stressed because of financial pressure.

- And 6 in 10 say it increases their sense of isolation.

“Rent is always our priority, then bills. But in London, the price of everything is going up. It’s been a challenge — we’ve had to go to our local food bank.”

Parent interview

Earlier this year, Toynbee Hall published “The crisis makes us more alone”, a report led by 12 brilliant young peer researchers from low-income backgrounds in Tower Hamlets. Their work explores how the cost-of-living crisis is affecting young people’s mental health. The findings are just as powerful and just as worrying:

Earlier this year, Toynbee Hall published “The crisis makes us more alone”, a report led by 12 brilliant young peer researchers from low-income backgrounds in Tower Hamlets. Their work explores how the cost-of-living crisis is affecting young people’s mental health. The findings are just as powerful and just as worrying:

- Over half of the young people surveyed had experienced rising stress within their immediate families.

- Nearly half said their own mental health was getting worse.

- These issues are compounded by financial insecurity, overcrowded housing, and insufficient mental health services, creating a web of challenges that many struggle to navigate.

These two reports, focusing on different stages of young lives, tell the same story: poverty and poor mental health are deeply intertwined.

Struggling to make ends meet doesn’t just fray people’s nerves, it isolates them and makes it harder to access help.

But there is hope - and it lives in our communities. Both pieces of research show the crucial role voluntary and community organisations play in offering support, connection, and understanding. These are the safety nets too often missing or even undermined from national policy.

We don’t need any more proof that poverty damages lives. What we need is action. We need policies that recognise that mental health isn’t just about individual resilience - it’s about the social and economic conditions we create.

Guest Blog with Z2K on the damaging impact of London's temporary accommodation crisis

Photo by Cyrus Crossan on Unsplash

Photo by Cyrus Crossan on Unsplash

Hear from Louise* and Miracle, two peer researchers with lived experience of temporary accommodation (TA) who co-produced Z2K’s research report ‘Frozen in Time’. The researchers interviewed people living in TA in Westminster about the issues they face and the impact that living in TA is having on peoples’ lives. The research was launched last month at an event in Parliament hosted by Rachel Blake, MP for Cities of London and Westminster.

Miracle: My first experience of homelessness and temporary accommodation was in London during my late teens for about two years. For a young man with the ambition to hopefully do well in the world and succeed through education, those two years for me were really traumatizing (fighting forces of derailment with a strong will and focus to triumph through). The overall experience I had during that period of time involved living in bad housing conditions (mould, damp and pests) causing health issues, as well as the impact of burglaries. However, I went through adversity those two years and conquered it with cheerful spirits of hope for a better day someday. Since this time, I have had a nomadic existence because I had nowhere that I could call home in the UK. I moved from TA to a mixture of student accommodation and privately rented accommodation. More recently, I have found myself back in TA, placed in a hotel ‘out-of-borough’.

Louise: I lived in TA as a single parent placed out-of-borough. It felt like screaming in a sound-proofed room, hoping someone might hear. I felt exhausted from fighting to pin down who was responsible for the infestations and damp in the property. For my child, living in TA meant having a stressed mother whose spare time was spent chasing the council, growing up in an environment which did not allow pictures on the wall, pets, or any self-expression or personalisation – and no playdates due to the damp and disrepair.

Miracle: It has been a rewarding experience being a peer researcher on the Z2K temporary accommodation project. Working on the project and meeting like minds with shared experiences was for me a great opportunity to help dig into the heart of the TA experiences which many in Westminster are currently having. It has been satisfying to try to bring this reality closer to the eyes of decision-makers at Westminster City Council.

Louise: Interviewing people who had been placed in TA by Westminster City Council as part of the research project was the first time I had spoken to anyone else in TA about their experience, and the interviews immediately made me feel less isolated and more human again. I found it validating and cathartic to speak to others facing similar difficulties.

Miracle: It is clear to see from the findings that people living in Westminster TA desire more empathy and understanding.

Louise: In temporary accommodation you are always on the verge, on tenterhooks, never knowing when you’ll get told to leave. I felt helpless living out-of-borough, unable even to vote for the Westminster councillors who held my housing future in their hands. Then there is the stigma you fear if you share this with schools or GPs; the assumption you must have done something wrong to be in TA to begin with.

Miracle: There are a number of areas where change is needed, such as in the council’s engagement and communication with people.

Louise: All Westminster schools and GPs should read this report so they understand how TA affects their service users. Similar to my own experience, the vast majority of people I interviewed did not feel that their needs were met or understood. Whether it was complaints about damp and mould adversely exacerbating their health problems, or traumatised survivors of domestic abuse being placed in unsuitable accommodation, the common problem was the lack of communication and engagement on the part of the council. This left the interviewees, mostly women, feeling forgotten and as if they don’t matter.

Miracle: We need to see a change in the way in which people living in TA are often seen and treated.

Louise: The uncertainty and the worry of not knowing where or when they might be moved on caused families stress and insomnia, which affected their mental and physical health. This in turn affected school or work outcomes, despite trying their utmost to do well and succeed. Households needing temporary accommodation appear to be looked down on.

Miracle: For so many, living in TA is not temporary. Therefore, improving TA standards is surely an area where change is vital. I believe that the report will help to bring a dose of reality to the current understanding of temporary accommodation at Westminster City Council, so that there can be a different tomorrow.

Louise: I believe that if the council staff had carried out the interviews we did, and experienced the resilience and tenacity of these people, then they would treat them with more respect, inclusion and engagement. Meaningful dialogue, not stonewalling, is what is needed to free people living in temporary accommodation from the state of limbo that they find themselves in.

*Not her real name

The tragic relationship between child poverty and homelessness in London

Photo by Pedro Ramos on Unsplash

The threat of homelessness is an extremely visceral fear. The lack of a safe place to sleep, eat, shelter from poor weather and gather with those closest to us should be a basic right that every individual sees realised. However, for thousands of children their home is just a hope. In the meantime, they might sleep in mouldy, cold rooms, while sometimes sharing a hotel bed with several siblings with nowhere to play or do homework.

At the end of February this year, the government released new statistics for July to September 2024 showing that 70,450 households in London are in Temporary Accommodation. Focusing exclusively on all households with children across the country in TA, 58% are in London alone. As Shelter, recently highlighted, 164,040 children are currently in TA and 92,850 or nearly 3 in 5 children in TA are in London. These children are not well captured in HBAI data, which is used to create child poverty statistics for the country. That could mean that nearly tens of thousands of children are missing from the estimated 700,000 children believed to be in poverty across the capital. We also know that children are being moved outside of their local borough or even outside of the city entirely, but we don’t know how many.

With the equivalent of one child in every classroom in London currently living in temporary accommodation, and 14,885 young people presenting as homeless to their local council across the city in 2023-24 figures, it is clear that all levels of government across London must take the intersection of the housing crisis and child poverty very seriously.

Gathered evidence shows that child poverty can be a predictor for adult homelessness and is almost always a co-existing reality for families facing the threat of homelessness.

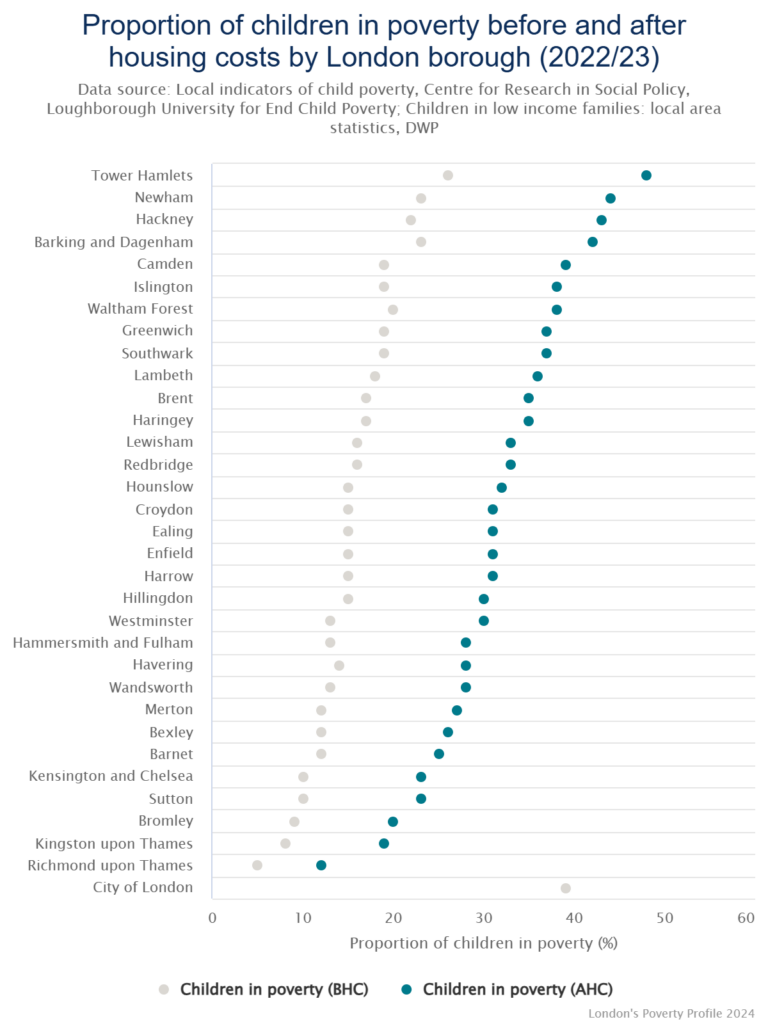

Trust for London’s 2022/23 data on child poverty rates after housing costs show significant jumps when housing costs are accounted for as the chart below shows. The affordable housing crisis in London and the hundreds of thousands of children experiencing poverty must be viewed in tandem. If we want to seriously prevent child poverty from causing long-term harm to children, we need to build appropriate, truly affordable homes fit for families who live in our community urgently.

The challenge though to quickly improve the lives of families is to provide the services they need when the threat of homelessness first looms. There are particular groups who face specific barriers when navigating personal crisis. For a parent who is threatened with domestic violence or a single parent with threats from debt collectors or joblessness due to unpaid caring responsibilities, holistic support is needed to help prevent and reduce the likelihood that they are unable to stay or move into a permanent home quickly. Other families are essentially forced into homelessness after their application for asylum is approved and they’re granted refugee status. These families often have little to no social and financial capital. Those still in a visa application process also face costly fees and limited social security support should they need it. And if a person has grown up in poverty and either loses their home or must leave their current place as a young person, their age may limit both their eligibility for support and prioritisation for what little help they can request.

Effective interventions must tackle both the broad supply challenges as well as the specific individual circumstances of Londoners. If change isn’t built on understanding of individual needs, it will fail to create systemic change.

Certainly, the evidence is clear that building more truly affordable social housing is the cure. At the same time, we also need to inoculate ourselves against the disease of child homelessness in London urgently. This is a public health crisis and a moral indictment.

We are currently leading a project focusing on the key moments when homelessness should and could be prevented. We believe that some crucial conversations need to be had about protecting families from homelessness and providing appropriate support to shorten or prevent experiences of homelessness. The issues are complex, but inaction is costly. Children have significant health, academic and social risks if we do not act quickly. We’re privileged to be working with Cardinal Hume Centre and New Horizon Youth on this project. Together we’re gaining insight from three particular groups to understand what policies need to be put in place while the houses are still being built.

We’re currently interviewing young people with experience of homelessness as a minor or young adult, migrant families and single parent, women led families. We are holding these interviews across March and April. If you know of someone who might like to take part, please do get in touch.

We aim to share our findings in summer 2025 and invite political leaders and civil servants to engage in important conversations about how we can support families to reduce the backlog of cases where families are living in unacceptable circumstances and children are growing up without a home.

Visit to Restorative Justice for All

One of the best parts of the role of community outreach officer for 4in10 is the privilege of being able to visit our extraordinary members and this has led to some truly fantastic experiences.

Whether it is being part of the series of campaign events put together by Southall Community Alliance, watching the presentation of new bleed control kits, donated by anti-knife crime charity Bin Knives, Save Lives or being part of community information events run by Poplar Harca housing association, this job continues to give me the chance to really experience the hard work of our incredible membership and has given me a real sense of hope.

Given this I thought it would be good to write about one of these events to give you a flavour of the experience.

A couple of weeks ago I was lucky enough to visit Restorative Justice for All (RJ4All)’s Rotherhithe Community Centre whilst they were doing their Wellbeing Circle.

RJ4All is a charitable international institute with a mission to address power abuse, conflict, and poverty through the use of restorative justice values and practices. The RJ4All Rotherhithe Community Centre serves as a vital hub for community empowerment and social connection at the local level.

As RJ4All’s Community Centre is always doing events, so for me it was originally more the date I was available to go than what activity I was going to be part of, but I was so glad I chose that day!

When I arrived, I was instantly made to feel completely welcome and shown around their centre. This was a very friendly building made up of a few side rooms, an office, a small kitchen and a small meeting room with sofas, tables, chairs and toys for children.

I was the first visitor to join but the session quickly filled up and by the time we were ready to go there were maybe 10 of us (all women). It was only at this point that I was grew to understand the nature of the event.

Our team leader explained to us that the idea was that each week the wellbeing circle explored a thought-provoking topic with the leader posing questions within it. She then apologised as it was her first week – not that you would have known she was brilliant.

I would not say I was cynical about the model – group therapy has been shown to do some amazing things but I was unsure how I would find it with not knowing anyone or indeed anything about the event but any anxieties I had were soon to be proved wrong.

The topic under discussion was ‘forgiveness’. First we were asked to explain in turn what we understood forgiveness to mean and then went on to explore times where we had each grappled with forgiveness.

As we went round the circle the comments of my fellow participants began to really touch something in me and as the evening went on I found myself talking about things and feeling emotions that I would never have thought about. And this, plus being with others while they explored sometimes very personal things profoundly touched me.

I came away from that extraordinary event feeling incredible, refreshed and if possible lighter; like I had been on a big therapy session. I would recommend this experience to anyone!

RJ4All’s Wellbeing Circles promote its overall vision of building the world’s first restorative justice postcode by providing a first line of mental wellness support to the community, strengthening relationships within the area, and fostering community cohesion in SE16.If anyone else would like to learn more about RJ4All you can go to their website here [I’ll include a link when it goes live].

'Make Childcare Make Sense' conference at City Hall (21 January 2025)

Last week, we were thrilled to host our ‘Make Childcare Make Sense’ conference at City Hall, generously hosted by London Assembly Member Marina Ahmad. This event marked the culmination of two years of dedicated work, focused on the challenges families on low incomes in London face when trying to access affordable childcare.

Last week, we were thrilled to host our ‘Make Childcare Make Sense’ conference at City Hall, generously hosted by London Assembly Member Marina Ahmad. This event marked the culmination of two years of dedicated work, focused on the challenges families on low incomes in London face when trying to access affordable childcare.

Our work was driven by an urgent and growing concern—raised both within and beyond our network—that the soaring cost of childcare is a key driver of child poverty in London, rivalled only by housing costs. In response, we partnered with our network members to investigate these experiences in depth. The findings are detailed in our report, Make Childcare Make Sense for Families on Low Incomes in London, published in March 2024.

The report revealed that the current childcare system is failing families. Many funding entitlements are inaccessible due to required ‘top-ups,’ inflexible policies that don’t accommodate diverse circumstances, and a lack of inclusivity for all children. Parents deeply value childcare, but they find the system frustratingly complex and overwhelmingly expensive.

These findings align closely with other key reports published around the same time, including the London Assembly Economy Committee’s Early Years Childcare in London and Business LDN’s No Kidding: How Transforming Childcare Can Boost the Economy.

Our event last week, which was attended by a wide range of stakeholders, took stock of the situation nearly a year on. We heard powerful contributions from members of the Childcare for All campaign group about their lived experiences of childcare when you have no recourse to public funds, from Single Parents Rights Network and KIDS, who support families with disabled children to access childcare. All had clear and very pragmatic suggestions about how the system could do much better to support the groups they represent.

Rosa Schling from On the Record delivered a fascinating presentation on historical childcare campaigns, including the National Child Care Campaign of 1985, which called for “comprehensive, flexible, free, and democratically controlled childcare facilities funded by the state.” It’s striking how closely this aligns with what the parents we spoke to today still need and want.

We also heard from Sarah Ronan of the Early Education and Childcare Coalition and June O’Sullivan from LEYF, both of whom made a compelling case for an urgent policy shift. They emphasized that while the Government is making significant investments in early years education, these investments are failing to reach the most disadvantaged children. Failing to address this is an untenable position for a government that is committed to both reducing child poverty and improving early childhood development.

Finally, we were delighted that Joanne McCartney, Deputy Mayor for Children and Families was able to attend and address the conference; to hear directly from families, practitioners and researchers about the current challenges and we look forward to continued dialogue with her and the Mayor about what the GLA can be doing to both support the childcare sector and families and children to benefit from it.

If you couldn’t join us last week, we truly missed you—and we can confidently say you missed out too! But don’t worry—you can still be part of the conversation. Watch our campaign film, where parents dare to dream of a future where childcare is accessible to all children, free and on an equal basis: https://4in10.org.uk/make-childcare-make-sense-a-4in10-film/.

Childcare reform and tackling child poverty must go hand in hand

Early education and childcare has not been at the forefront of the last few elections but notably this time around it is a hot topic. All the main political parties seem to recognise, albeit from differing perspectives perhaps, that there is much to be gained from better supporting and investing in children in their earliest years. The Conservatives have re-emphasised their commitment to rolling out 30 hours of childcare a week to working parents with children from nine months old to when they start school by September 2025. The Labour Party have also pledged to deliver this same commitment and plan to open an additional 3,000 nurseries through upgrading space in primary schools to help them do so. The Liberal Democrats for their part say they would close the attainment gap by giving disadvantaged children aged 3 and 4 an extra five hours free a week and tripling the Early Years Pupil Premium to £1,000 a year.

The question we, as London’s Child Poverty Network are asking of all these offerings is whether they will benefit children and families experiencing poverty who at the moment are benefiting less from the system than their wealthier peers. Back in March we published a research report ‘Make Childcare Make Sense for families on low incomes in London’. In it we looked through the eyes of parents of young children living on low incomes in London and found that the current childcare system makes little sense to them. The funding entitlements were often not accessible as they couldn’t be used without having to pay ‘top ups’; they were not flexible enough to meet their individual circumstances; and were not inclusive for their children, those with special educational needs and disabilities and those whose families have no recourse to public funds being especially likely to be excluded. One single mum of a three-year-old told us:

‘You know, you’re kind of making lots and lots of sacrifices to afford what essentially is a basic need to help our economy keep moving. Yeah, [the childcare system] just shuts people out of work.’

Sadly, the Government’s expansion of funding entitlements which began to be rolled out shortly after our report was published in April this year, will do little to improve the situation for these families. Just 1 in 5 (or 20%) of families earning less than £20,000 a year will have access to the planned expansion of funded places for one- and two-year-olds in some working families, compared to 80% of those with household incomes over £45,000.[1] This matters to us because access to affordable, high-quality childcare and tackling child poverty are inextricably linked.

Sky high childcare costs in London are one driver of our high child poverty rate; including childcare costs in the Social Metric Commission’s measure of poverty increases the poverty rate among families with children by 0.4 percentage points.[2] So, at the most straightforward level, bringing down childcare costs, for those that already incur them, has the potential to reduce levels of child poverty. Beyond this, affordable and accessible childcare can contribute to poverty alleviation by supporting parents and carers to access paid work if they do not already or to increase their hours, and so increase their household income. Lastly but certainly not least, we know that high quality early education is critical to a child’s development and later educational achievement.[3]

For all these reasons, it is imperative that whoever forms the next Government deliver an early education and childcare system that benefits all children. We believe that the best way to make sure this happens is for childcare reform to be at the heart of a strategy to address child poverty. The Labour Party has made a very welcome commitment in its manifesto to putting in place a Child Poverty Strategy, it must make sure that its policy on childcare in a key plank of this. If it doesn’t and this synergy isn’t realised is a very real risk that childcare policy rather than reducing inequality, could increase it.

[1] Drayton, E. et al. (2023). Childcare reforms create a new branch of the welfare state – but also huge risks to the market. Institute for Fiscal Studies. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/ news/childcare-reforms-createnew-branch-welfare-state-alsohuge-risks-market

[2] Poverty Strategy Commission (September 2023) Interim Report: A new strategy for tackling poverty

[3] Melhuish, E. and Gardiner, J. (2023). Equal hours? Sutton Trust

A young person speaks: the Local Child Poverty Statistics 2024

By Layla, aged 19 from London (name changed to protect her identity)

I respond to this news not just as a young person, but as someone who has personally experienced the harsh realities of poverty. The recent findings from Loughborough University for the End Child Poverty Coalition resonate deeply with me, and seeing that over 30% of children across the UK are living in poverty, with two-thirds of new constituencies having at least a quarter of children facing this struggle, brings back vivid memories of my own childhood and the beginning of my own adulthood.

Growing up in poverty meant constant uncertainty and anxiety, and meant watching my care giver struggle to make ends meet, sometimes having to choose between paying bills or buying food. It meant missing out on school trips, new clothes, and being pointed out as the free school meals kid. What I’m trying to say is that these are not just statistics; they represent real lives, real struggles, and real futures at risk.

Hearing the call from the End Child Poverty Coalition for political parties to prioritise this issue fills me with a sense of urgency as it would not just be a policy change, but a lifeline for many families.

The disparities highlighted, especially in areas like the North East, London, and the North West, show that this issue is widespread and deeply rooted. It isn’t enough to just acknowledge the problem; we must act.

As someone who has walked this path, I urge our leaders to listen and to act. the upcoming election is a chance to commit to real, meaningful change, and ensuring that no child has to grow up feeling the weight of poverty, and having the opportunity to thrive is something every party should aim to include in their campaign.

Can a national child poverty strategy be all things to all children?

Well, just as we were drawing breath after the London elections, we find ourselves back in election mode once more. And once again we will be straining every sinew to ensure that child poverty is a central issue of the campaign and one that all the political parties are held to account on. In particular we will be making the case for all parties to pledge to a child poverty strategy that not only makes firm and time-bound commitments about reducing and ultimately eradicating child poverty but also recognises that achieving this aim will require different approaches in different parts of the country.

Of course, some of the key policies that we, along with over 100 other members of the End Child Poverty Coalition, want to see front and centre in a child poverty strategy such as abolition of the two-child limit and benefit cap, are ones that an incoming Government in Westminster alone can implement. But we also need a child poverty strategy that operates regionally and locally so that it can respond to the different contexts that children live in across the country. For example, in the North East child poverty is driven in large part by low pay, insecure work and out-of-work poverty (North East Child Poverty Commission, 2024), whereas in London it is exorbitantly high housing costs along with costs such as childcare that are the major issue. Important new analysis from our colleagues at Trust for London and WPI Economics exploring the possible reasons behind the apparent fall in overall poverty numbers in London in the past few years, suggests that costs are now so high that for many people the only way to escape poverty in our city is to leave it.

A national child poverty strategy that fails to recognise these regional differences and allow for differential responses is not going to have the impact it so urgently needs to. The incoming Government, must engage with and harness the data and knowledge that the Greater London Authority, combined and local authorities have about their regions and localities and establish mechanisms to ensure sustained focus and action on the issue at regional and local level. Moreover, it needs to recognise the impact that the collapse of local government funding has had on children’s services which has undoubtedly affected the poorest children most. It is crucial that a child poverty strategy ensures that local authorities are sufficiently resourced to meet the needs of the children living in their communities.

So, in answer to the question, yes, a national child poverty can and must deliver for all the UK’s children, no child wherever they live should be experiencing poverty, but this will only be achieved if we acknowledge and respond to their different circumstances. From our perspective as the London Child Poverty Network, we will use the coming weeks to champion as loudly as we can the right of the 700,000 children living in poverty in London to live in a poverty free city, a goal that we firmly believe is achievable if the political will is there to achieve it.

Tackling child poverty must be high on the new mayor's agenda

Yesterday Londoners went to the polls to elect their Mayor and members of the London Assembly. As we await the results, it is a good moment to pause and consider what should be at the top of the Mayor’s agenda from day one of their new term of office. From our perspective at London’s Child Poverty Network we are crystal clear that tackling the high levels of child poverty that continue to mar our city must be up there.

The first crucial step towards bringing about a child poverty free London must be to work with those children, families and those organisations who support them in their communities to develop a strategic response to tackling the problem over the next four years. As a network we have been very supportive of Sadiq Khan’s move to guarantee free school meals for all primary school children in the city, which demonstrates that he gets the severity of the situation and the need to take bold action to address it – but we know that on its own, it is not enough. Now is the time to bring everyone to the table to decide what other actions need to be prioritised to address the systemic causes of poverty. And we are not the only ones saying so, just before the election period began back in March a cross-party group of London Assembly Members supported our call and published a report recommending that ‘[t]he Mayor, working in conjunction with local authorities and the voluntary sector, should publish a child poverty strategy for London in 2024-25.’

So, what are the key policies the strategy ought to contain? Well, it is a fact that many of the levers for reducing child poverty lie beyond the direct powers of the Mayor of London; our broken social security system for example, which exacerbates rather than ameliorates child poverty rates by setting benefit payments at levels which are not sufficient to provide families with essentials; discriminates against larger families through the two-child limit; and imposes sanctions that push families into debt rather providing them with the scaffolding they need to escape poverty. These are not policies the Mayor can directly change, although they can add their strong voice to the chorus of cries for reform.

Where the Mayor can take direct action though, they must. Child poverty in London is driven in large measure by the exorbitantly high costs of living in the city, housing first among them. Without access to decent housing, 84,940 children in our city are living in temporary accommodation, often deprived of basics such as access to a hot nutritious meal, a warm comfortable bed and space to play and learn. Whoever emerges victorious from the election count will already be well aware that sorting the housing crisis is going to be one of the biggest challenges they face and indeed all the main candidates have pledged to do so, in various ways, during their election campaigns. What we are calling for now is for these efforts to also be a central plank of a new child poverty strategy for the city. By looking afresh as the problem through this lens we can ensure that the housing that is built truly meets the needs of young families living on low incomes and enables them to live in and contribute to our city, as part of our communities rather displaced to other more affordable parts of the country.

Addressing high childcare costs must be part of a London child poverty strategy too. In our recent report Make Childcare Make Sense we looked at how sky-high childcare fees disproportionately affect families living on low incomes making it next to impossible for them to stay and/or progress in work and how an inclusive, affordable childcare system could vastly improve their and the children’s lives and allow them to contribute to London’s economic well-being. Getting the national childcare and early education policy framework right is essential to achieving this goal but so too is leadership and intervention at the London-wide level and our report sets out a series of recommendations for the Mayor and GLA.

Faced with these high housing and childcare costs, another reason many families in London struggle to make ends meet is a lack of high-quality, well-paid work; in London, almost half of those in poverty are in employment and in 2022, 17% of Londoners in work were paid below the London Living Wage (Trust for London). Many of these also face the issue of insecure work. Recent research from the Living Wage Foundation has found that there are over 800,000 insecure jobs in London. Addressing these twin issues of low pay and insecure work must be another strand of a child poverty strategy.

Finally, is also crucial that a strategy recognises the interaction between poverty and discrimination and has addressing it at its core. We cannot for example, ignore the fact that systemic racism and disablism in the education system often combined with the impact of poverty, is responsible for holding back some of our young people and preventing them from flourishing in the way they should. A child poverty strategy rooted in a human rights-based approach is key to achieving deep and lasting change.

So, once they have had a chance to catch their breath, we hope our newly elected Mayor will engage with us as a network, draw on our members’ rich and diverse experience and work with us to map out and deliver a plan for achieving a child poverty free London; an achievable goal if we all harness our collective determination and belief to make it happen.

Voter ID and Shout Out UK

A few months ago there was a change in how elections are run in this country, when the Elections Act 2022 came into force

The Act bought in a wide range of changes that will have an impact in London including removing second preference voting in Mayoral contests, but arguably the biggest change was the introduction of compulsory voter ID.

This was trialled in the local elections in May this year to mixed success. The Electoral Commission’s full report is not due out till September but their initial findings have been so troubling that they have released an interim report. This can be found here. The biggest takeaway for me from this was that 14,000 people were not able to vote as a direct result of these changes.

The most significant reason for this does seems to have been lack of awareness of the new rules – only 84% of people knew about the new requirements according to the interim report. I would here quote a family member who when reminded of the need to bring ID said ‘well I never have to in the past’.

Another issue which is of particular concern for us in 4in10 however is unequal access to the right forms of ID. The House of Commons Library produced a report in which they said:

‘The proportion of respondents to the Electoral Commission’s Public Opinion Tracker 2022 who did not have a suitable form of ID for voting was higher among more disadvantaged groups. 14% of unemployed people, 10-17% of those living in rented local authority or housing association accommodation and 7% of people with lower levels of education did not have a suitable form of ID.’

Indeed the interim report found that two of the groups were awareness was lowest was among younger age groups (18 to 24-year-olds) and Black and minority ethnic communities which were both at 82%.

Valid forms of ID

The other issue that continues to be of concern is the types of valid ID. The list of ID that is accepted can be found here.

If you have a look at this list, one thing that becomes immediately clear is that the majority, if not all, of the options available cost money to obtain – a passport for example costs a minimum of £90 once you take into account the cost of the photo.

Some would then counter with the fact that in theory you can obtain a ‘free’ form of ID from your council but even this isn’t completely free as you are expected to bring a passport style photograph with you.

For some families that are already having to choose between heating and eating, paying for a photo to be produced and then spending time finding and filling in a complicated form simply can’t be a priority.

This can be shown in that awareness and take-up of the Voter Authority Certificate (a free voter ID document you can apply for) was low with only 89,500 certificates being issued around the whole Country according to the Electoral Commission’s interim report.

The London Context

London already has one of the lowest voter registration rates in the UK and these changes has the potential to make this situation considerably worse.

There are many reasons for this but one of the biggest is the high proportion of ethnic minority communities in London. Voter registration tends to be lower in ethnic minority communities. This is the case for many reasons, including in particular insecure, short term housing but no matter what the cause the result remains the same.

We at 4in10 are concerned that unless more is done to raise awareness of the new rules and to make it easier and cheaper to obtain the necessary ID, then Londoners who are already at most at risk of being disenfranchised will be denied the right to vote.

That is why over the last few months we have been supporting Shout Out UK who have been leading the public awareness campaign on this issue and we will continue to do so.

We are asking our membership to help us and Shout Out UK by spreading the word about it and where possible help people to get the ID that they need. Find out how here.

Child Poverty in London: a societal problem calls for community-led solutions (Part 3)

Our Research and Learning Officer, Emily, discusses three questions on the issue of child poverty in London. This piece is split across three blog posts:

- What is child poverty?

- What’s the state of child poverty in London?

- How do we end child poverty?

How do we end child poverty?

This is a big task. Let’s say tomorrow the government printed money and gave it to every family under the relative poverty line and promised to keep sending them money to ensure they never fall below that line, would child poverty end? If that question were posed to different politicians and members of the public, I’m sure several revealing answers would emerge. The reality is that things are much more complicated than just money. But as a start, money really does help. The £20 per week uplift to Universal Credit that was temporarily put in place during the pandemic pulled 400,000 children out of poverty. Other estimates claim that making this permanent would lift 500,000 children out of poverty. So money must be part of our child poverty strategy. So too would other public systems. Having an adequately sustained NHS and mental health services would keep children and their parents well, which cuts costs, both in terms of health itself and the knock-on effects of poor health.

Flexible working could also be seen as a support structure to allow adults, particularly women, to work consistently and progress in their careers while also caring for their children. And there’s also the housing issue. In London housing is incredibly expensive and too many affordable options are unsuitable. Guaranteeing affordable homes for everyone can be seen as part of a child poverty strategy.

So it’s about money, but it’s also about a community-based strategy. We need to eradicate the shame. There is no reason to judge people. Ending shame is not ending personal responsibility. Ending child poverty requires us to work together. It means believing the evidence that shows the causes of inequality and poverty are multiple and intersecting. It also means, perhaps, as a community taking on the shame that we don’t yet know how to support each other well enough. Privilege and discrimination has blinded many of us to our own personal responsibility. We can do better at that, but we need to be honest about our role and how we can learn to support each other more holistically and with respect.

4in10, London’s Child Poverty Network is committed to supporting collaborative working. We are a network of organisations who want to see an end to child poverty in London. There is so much brilliance bottled up in the children of this city. When we invest in them and make sure each of them has an opportunity to thrive, then we will begin to see transformations that we will all benefit from.

London’s Child Poverty Alliance, the policy sub-group of London’s Child Poverty Network has identified four key areas that can be catalysts for change. In our Manifesto, we outline current areas of inequality and systemic failure that are points of potential transformation that could ultimately bring an end to child poverty in London. Secure, adequate income will give families the resource to access what they need. All across London, our homes are fundamental to our health and wellbeing. When our homes are of decent quality, the comfort and security they provide enrich our lives and support our mental and physical health. Every child deserves the best start in life, ending child poverty means ensuring every child has access to the early education and childcare to thrive. Lastly, having access to nutritious and reliable food sources so that all children are free from hunger can target one of the essential threats of child poverty. Together, we can make child poverty a way things used to be rather than how we live now if we target these four areas as crucial pinch points of poverty to make London a fairer city for every child.